The Legend of Zelda is a massive video game series that spans decades. The original game was released thirty years ago and introduced the swashbuckling hero of time—Link—who must save the titular princess from evil Ganondorf. Wandering through the land of Hyrule, the player must explore and discover a plethora of secrets. The original Zelda game was the epitome of open-ended adventure, but now the series has become a locked game driven by story points and necessary events. However, there are many who relish this style of gaming and enjoy playing each installment in the Zelda series. I interviewed a self-described Zelda fan to understand why he plays the games and the gratification they bring. I wanted to know if these games were an opportunity to explore, or a chance to be guided along the story path.

Interviewing the fan William, I discovered a little about his play style and why the Zelda games appealed to him. He devotes small portions of time to the game, but he plays almost daily as an escape. In his own words he plays “to escape; when I’m stressed, to take my mind off of things that I should worry about.” It is a part of his return from school, a habit he’s recently developed. To this fan, Zelda is world to be explored with tasks and quests to accomplish. He gets very animated and excited when discussing the games.

But when asked why he plays Zelda, William reveals that these games are very purpose driven, which bleeds over from his personal life. He seeks to feel accomplished by finishing quests. Before he sits down he makes goals like “in my 30 minutes I’m going to finish this dungeon, or make a dent in this quest.” Instead of seeking a carefree, open release from responsibility, William thrives on an escape that is goal-orientated and structured, much like his personal life and obligations. He spoke about the other side of the coin, games are freer, open ended, and unshackled to story. “In those games I don’t feel like there is a purpose and I don’t enjoy them as much. Because there are infinite options, there are infinite paths, and since there are infinite paths there is no path. You just do whatever you want, but you don’t go anywhere.” Zelda is a release valve on the pressures of his life, but William still needs to feel like his video game has a purpose. He needs to go somewhere and do something, instead of aimlessly drifting. He repeatedly emphasized how much he likes progression, of moving towards a goal. Even if every Zelda game is a string of McGuffins, William still enjoys feeling accomplished. He accentuated these points with hand gestures to symbolize the progression.

But despite wanting these milestones and guidelines to progression, William’s main enjoyment from Zelda is in the action. He is not too keen on the story and admits there are others out there who are interested in the lore. Rather, he just wants to hack and slash and save the world. “I’m more into the action and killing things.” He loved one of the games, Skyward Sword, because it mastered the combat system. He admitted to being annoyed by anything that stops him from moving on and fighting monsters. From multiple responses, it became apparent that his favorite activity in Zelda is slaying monsters. This mentality feeds into his need to feel accomplished. With combat, your skill and accomplishment are evident and easy to gauge.

When asked about how to improve the game, William was silent for a while. He gathered his thoughts, mentioned some minor mechanics that could be tweaked. However, a lightning bolt hit him and he then divulged a dream that aligned with his previous attitudes. William mentioned that an additional hard mode would benefit the game. This would only be available after completing the original quest, and include monsters that were more difficult. Again, his draw to Zelda is apparent because it blends action and adventure into his questing and item collecting. He wants a goal-orientated game that ends with the ultimate battle of a major boss. When asked to describe Link, William mentioned that the hero of the game is quiet. William thought the protagonist is mute because he is not here to chit-chat, but to save the world.

This comment seemed to be a reflection of William’s feelings about the game and what he wants. The protagonist is noticeably silent in the games, to the effect that Link becomes a blank slate for players to insert themselves. When asked how he connects to Link, William mentioned:

Everybody has that childish dream of running around and abandoning your work and responsibilities and going out and slaying monsters and questing and going out and exploring. Too often we feel tied down with work, school, kids, it’s nice to kinda [sic] have a pretend world where you don’t have to pay the bills. You can chop up grass and find rupees, you can throw bombs at rocks and blow things up. Do fun things.

His comments about abandoning bills and responsibilities and to explore echoed his previous comments. William again emphasized what he likes in Zelda games by mentioning acts of violence: slaying monsters, chopping grass with your sword, blowing up rocks with bombs.

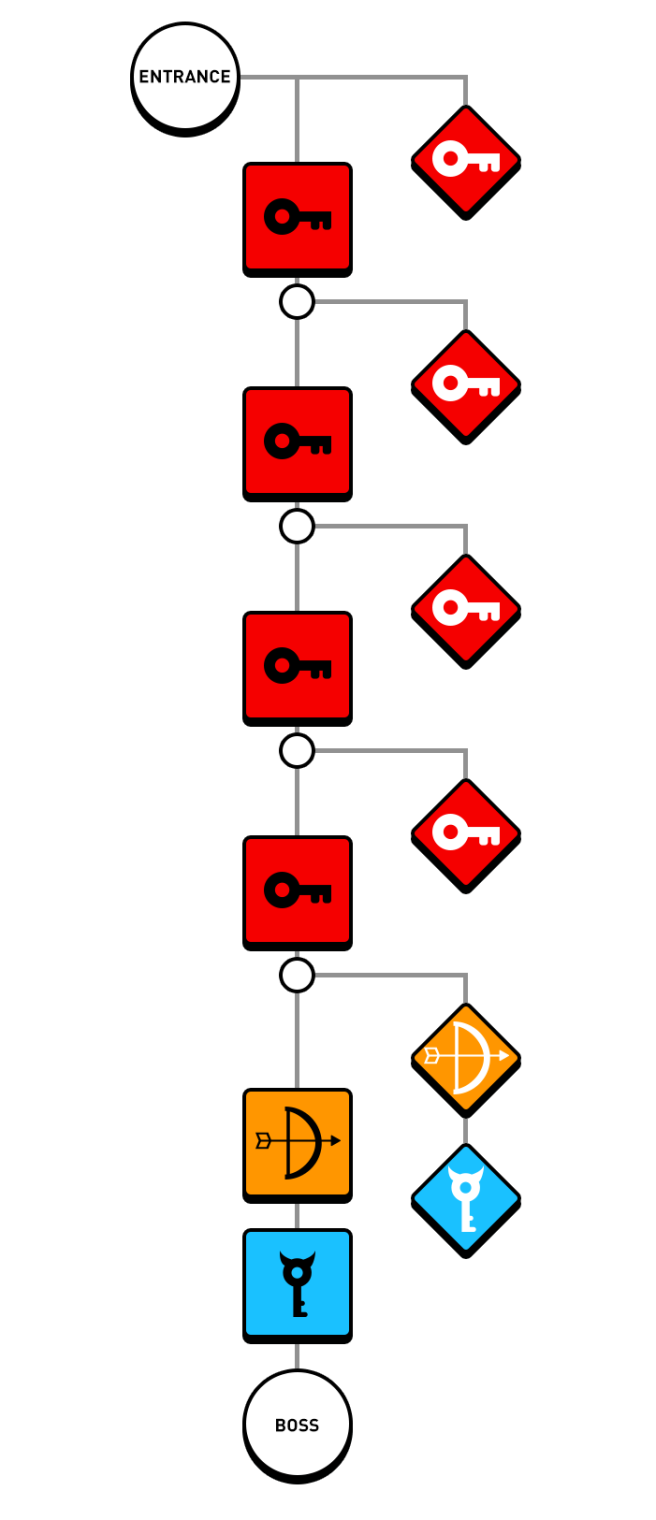

William also mentioned that the Zelda series is eternal. The games are formulaic, but that comforts him. He likes knowing that when you pick up the game you are going to get a game very familiar to the others. The patterns are not only acceptable, but required for his enjoyment. He listed these repeated elements: the same major villain (Ganondorf), monsters in dungeons, items to collect in the dungeons, and mini-bosses. These constants that he listed fall into the same themes of progression and action. William thrives on the formula because accomplishment drives his gratification. He stated that everybody knows the conflict between Ganondorf and Link in the Zelda games have been consistently great. “You’re not disappointed with a Zelda game. They always deliver.”

Each game is a remix of the previous one. While the story is more or less the same, there are minor tweaks. The Zelda series is not a traditional series in that the stories are connected, but there are multiverses and reincarnations. And yet William loves that every time you play a Zelda game, “it’s still a little boy dressed in funny green clothes.” It is okay for Link to go out and have his own adventures because he’s an orphan who does not have a mother waiting for him at home. He is free of family connections and responsibilities, a trait that William might envy.

When probed about what elements of the story are memorable William mentioned that part of the story is saving different villages and areas from a big-bad monster and being applauded for it. As Link you enter one region after another, fix the problem, and the become the hero of that area. William’s comments reveal a Savior-complex, which the game encourages.

During the interview William’s toddler nephew starts playing with the Zelda game and console. William gets worried and is obviously concerned about the game cartridge. To William this game is very old and delicate. His distress over the safety of his game reveals a lot about his connection to this portion of his childhood. He is reliving this game many, many years later to find closure. He never beat it all those years ago. In William’s closing comments he reveals his dream to play Zelda with his kids one day. He wants to share these memories and be a cool dad who also plays video games.