Below is a chapter from my upcoming book, The Symbolism of Zelda: A Textual Analysis of The Wind Waker.

Being released on a new console—the GameCube—meant that The Wind Waker could take advantage of the new and improved hardware. One of these improvements included a drastically better sound card, allowing for improved music. While it wasn’t technically fully orchestrated, the MIDI-based instruments sound much better than the N64 scores 1. While some of the track fall flat, none of them sound intolerable.

Another change in this game is the number of composers involved in the production. While most games usually only have two or three composers, due to the rushed development schedule The Wind Waker had five to six 2. With more composers working on the score, the themes and motifs were expertly crafted to build the tone of the game.

But improved sound cards and a larger compositional group were not the only changes to the Zelda formula with this game. The new landscape of Hyrule also changed the musical landscape. With Link no longer exploring on foot or horseback, the sea had an impact on the music. You can hear the natural ebbs and flows in the soundtrack, reflecting travel by boat 3. The motif of the Great Sea reflects this new direction, with a natural rhythm that mirrors the waves of the ocean.

Listening to it countless times, I’ve also found other trends in the score. What strikes me most about the soundtrack is its length: 133 tracks spread over 2 CDs. Most of the tracks are short—merely jingles that represent different accomplishments in the game. But even the “real” songs are rather short, leaving you to wonder if they could have been longer if the SFX were cut from the CD 4.

While I wish these fanfares and jingles were excluded, this is still a great soundtrack 5. There are great songs, and good ones as well, and this chapter outlines some of the strengths of music as an important element of the game. I’m going to refer to the soundtrack a lot, so if you don’t have access to a copy of it, do a quick Google search and listen to it as you read this chapter.

The Legendary Theme

As an iconic piece of pop culture, The Legend of Zelda series has memorable music. Across the series, the score is always a principle and outstanding element of each game. There are two selections of game music that I listen to regularly, Metroid Prime and the Zelda games. In particular, I enjoy the Ocarina of Time, Wind Waker, and Twilight Princess soundtracks, which served as creative inspiration while writing this book.

The creative mind behind the music for Zelda has been Koji Kondo, a man who has also shaped video game music through his gift of the Super Mario Bros. theme. With his understanding of motifs: unity, and the stickiness of music, Kondo has been able to leave a lasting legacy of good music within the series 6, which has a history of maintaining a singular message and pattern within the music.

As discussed in the previous chapter, this game series is about exploration of a fantasy world. And since each game is part of a larger mythical world, the primary musical theme evolves but remains the same. The “Overworld Theme,” also known as the “Hyrule Field Theme” exists in every single game in the main series 7, and is repurposed in The Wind Waker as the “Great Sea Theme.” Even with the changes in the environment, this installment still adapts the classic theme.

The Wind Waker also borrows songs from Ocarina of Time (as it takes place 100 years after the events of that game) and A Link to the Past 8. The “Master Sword,” “Cave,” and “House” themes are borrowed wholesale from Ocarina of Time, with new arrangements on the “Zelda” and “Fairy Spring” themes 9. There is even a reimagining of the title screen music from A Link to the Past that makes its way into the game 10. Again, these fan favorites and songs carry nostalgia while also bringing thematic unity to the game.

Probably the greatest piece in this score (and my favorite) is “The Legendary Hero.” It is an acoustic, stripped down version of the above mentioned “Overworld Theme,” while blending in a new harmony and additions to the melody 11. This song is emblematic of the musical tone and theme of the game. This song adapts the classic and strips it down to the core, while also adding a fresh layer to the harmony.

This adaptation of the Zelda legacy, while bringing new life to it, grounds the game as a myth. Legends and myth are stories that never leave our culture, as they find new life in reimaginings and interpretations. If each game brought completely new music—without the motifs and themes from before—the Zelda series would feel fragmented and disjointed. But with the continuation of the iconic tunes, these games are unified and grand.

Starting Your Quest

The first song you hear is the most important one. The opening sequence is the hook for The Wind Waker, and its superb direction is what sets the stage for the fun and adventure that awaits you. The cheerful, striking melody is played on the harp and gentle percussion. This plucky sound establishes a clear rhythm and is strengthened with additional wind instruments and strings as the tune progresses.

This intro song has Celtic roots, with a strong Irish influence with uilleann pipes 12. These wind instruments sound similar to bagpipes and add flavor to the song as part of the harmony. The song starts with quarter notes but jumps into eighth notes, and this jump in the musical tone makes the song great for dancing. This musical momentum leads you along as the player, encouraging you to start your journey.

But this is not the only song in the game that uses unique wind instruments. “Dragon Roost Island”—another favorite of mine—has a beautiful pan flute and guitar combination. This excellent pairing of instruments is reminiscent of Andean music, and this mashup brings yet another cultural flavor to the soundtrack 13.

The combination of pipes and percussion are a strength of this soundtrack 14. Because Kondo and the other composers used percussion appropriately, they were able to create lasting rhythms within the melody, ones that would last long after you have turned off the game. This stickiness of the sound makes the game great. The importance of rhythm can’t be overstated, as it is the skeleton of the song and the foundation of the gameplay atmosphere.

Leitmotif

A leitmotif is a short, constantly recurring musical phrase associated with a person, place, or idea 15. It is used masterfully in The Wind Waker, as many of the songs are associated with characters or events, and these musical themes are brought together at key times in the game to harmonize the story. One of the first viral videos on YouTube was “Wind Waker Unplugged,” which demonstrated the use of leitmotifs in the title song.

An excellent example of the leitmotif is Howard Shore’s score for The Lord of the Rings trilogy. While the movie series contains hundreds of musical phrases or themes, it also adds orchestration and modifies the themes so the music tells a story 16. Evan Puschak noted how this adaptation and evolution of the Fellowship Leitmotif adds and builds upon the story of the movie 17.

Within The Wind Waker the wind and earth songs, as played by the sages Medli and Makar, serve a similar purpose of evolving the soundscape alongside the story. When Medli and Makar are awakened to their role as the Earth and Wind sages, respectively, they perform a song in a cutscene that is a variation on their player music. As these two characters play a central role in the game, it is fitting that their prayers are melodies that merge for the songs that bookend the game 18. Let’s examine how this leitmotif tells the story of Medli becoming the sage of the Earth Temple.

As a player, you first learn the “Earth God’s Lyric,” which is an event song used to unlock the Earth Temple. It feels familiar, and the melody is memorable. After learning this song, a cutscene plays where you meet the ghost of the previous Earth Sage, Laruto. Despite her death, she wants you to find her successor who wields the same harp. During this cutscene, you hear the song “Sage Laruto,” which introduces the Laruto Theme, which merges into the “Overworld Theme.” At first, these two themes are barren, sung by a vague MIDI-like chorus, but layered upon with an added harp melody.

Figure 1: Laruto Theme, from the song “Sage Laruto”; retrieved from NinSheetMusic.com

This song has an otherworldly feel to it, from the chorus and the somber harp. But it also establishes the character of Laruto perfectly. Her ghost comes from a previous, but familiar timeline, hence her alignment with the “Overworld Theme.” But her harp is the link that connects her to Medli, and this instrument is key to both of their characterizations. Thus, this song moves the story along in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

When you do find Medli, she is strumming her mirror harp on Dragon Roost Island, her sour notes overtaking the environmental music of the area. Her attempts to learn the harp makes sense, as you realize that it is the same harp from the vision of Laruto. And when you play the “Earth God’s Lyric” to her, there is another cutscene to explain her awakening. Music moves us, and in this moment, we learn how it has moved Medli. She realizes that she has been called as the sage of the Earth Temple, a calling that feels right. And as she realizes this, the song “Medli’s Awakening” plays.

This song begins with the Laruto Theme, in the eerie MIDI-like chorus, but fades into the “Earth God’s Lyric,” as Medli plucks hesitantly on her harp. She wavers, and then the ghost of Sage Laruto joins on a harmony harp, with the theme adding more vocals in the background. Then, the song fades into a minimalist, somber version of the “Dragon Roost Island” song, or what could be called the Rito Theme.

Figure 2: “Earth God’s Lyric” from NinSheetMusic.com

In this one song, we see the development of Medli as a character. The Laruto theme represents her history and her calling, and as she listens to her heart she able to overcome her weakness and fulfill her destiny. As she struggles to find her way and hesitates over the notes, the ghost of her ancestor comes to her aid. This addition from the previous sage adds depth to the music, making it beautiful. But as Medli realizes the responsibility of her future, the cares of her current life ebb back into her mind. By becoming the next Earth Sage, she will give up her life on her island to help Link defeat Ganondorf. Over the course of this song, she matures from a child into a woman and does so powerfully.

But Medli follows Link into the Earth Temple, and together they master some puzzles. After Link has defeated the boss, one more cutscene plays wherein Medli performs her prayer to strengthen the Master Sword and weaken Ganondorf. In this song, “Medli’s Prayer,” the leitmotif continues to build, and it was in this moment that I realized why the “Earth God’s Lyric” was so familiar: it is part of the title song. In this cutscene, Medli is again joined by Sage Laruto, with the gentle addition of the Celtic pipes, followed by strings, until the song is complete. Medli’s part in the “Title” song and the game has finally settled 19.

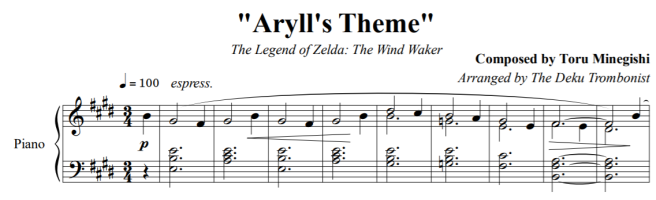

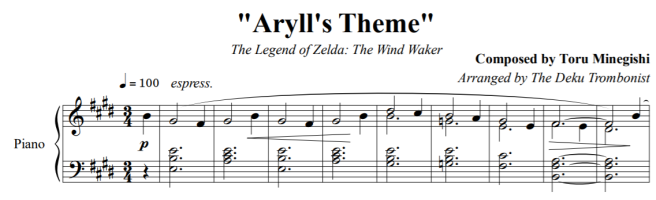

Makar’s character follows a similar pattern, with the ghost of the Wind Sage, and Makar’s awakening and prayer songs. Through these songs, and their accompanying cutscenes we see Makar awaken to his destiny and gain the courage necessary through the masterful use of leitmotif. But “Aryll’s Theme” is another memorable example of the use of leitmotif in this game. The theme established for Aryll, Link’s sister, is an upside-down version of “Zelda’s Theme,” a classic song from previous games:

Figure 3: “Aryll’s Theme” retrieved from NinSheetMusic.com

Figure 4: “Zelda’s Theme” retrieved from NinSheetMusic.com

This bouncy theme is used on three different occasions. It is first introduced when Aryll is kidnapped by the monstrous bird in the first chapter of the game. Due to the kidnapping, the song is cut short right before its resolution, giving a sense that Aryll’s life might be cut short (surprise, it isn’t). The theme is a combination of methodical strings, until the kidnapping, where the tempo and urgency are increased. Next time we hear the theme is when Aryll is rescued, and this time it is performed on xylophone and pipes, a fun and childish, but comforting, song of reunion. And the third occasion Aryll’s Theme is used, it is masterfully combined with the themes for Makar and Medli in the magnificent symphonic finale 20. The game ends with the combination of all three characters, a powerful end to the story.

This score masterfully tells a story through its usage of leitmotifs. However, this is not the only strength of this soundtrack. It also weaves interactive elements to play alongside the actions of the player. This soundtrack becomes an example of adaptive music, a burgeoning art form that takes the soul of Jazz to new heights. In order to do this, the score had to be divided into a hierarchy to create a logical system for combining the sounds.

Types of Music

Within the game, there are three types of music: environment music, event music, and earcons. Environment music is the background music for different locations and is always looping. Examples are the songs for Windfall and Dragon Roost Islands. Next comes event music, which is any song played during a cutscene or non-playable event—such as the Title Song or End Credits. This also includes the songs played on your baton, as they play once, and are tied to an in-game-event. The last type of music are earcons, which are brief, distinctive sounds to represent a specific event or convey information—such as picking up rupees, or opening a treasure chest. These sound effects don’t loop, and are typically very short.

As mentioned earlier, these three types of music form the system for an adaptive score. There is a hierarchy, where environmental songs can be interrupted by event music or overlapped by an earcon. Understanding the possible layers of these sounds allows us to examine the various crossfades that happen to allow the adaptive game score.

Adaptive music

Mark Brown in a video from his Game Maker’s Toolkit series, discusses examples of adaptive music found in popular games. He claims that Nintendo is obsessed with adaptive music, sneaking it into the Mario and Zelda games 21. Examples of adaptive music include subtly changing instruments or adding new ones when you change location within the shop in Skyloft and Skyview Temple in Skyward Sword. Brown also notes that in Spirit Tracks, the music increases in tempo when the train speeds up. In the Spirit Tower, more instruments are added to the song as you ascend, giving an epic feel to the adventure. And in Mario Kart 8, portions of the song change as you transition into different legs of the race 22. These adaptive songs help Zelda games feel epic and add character to the world.

In Medina-Gray’s dissertation (2014), she examines the strengths and organization of adaptive music within video games. In her analysis, she creates game score graphs or a visual representation of how the soundtrack flows together. I have taken a similar approach to the music within The Wind Waker, to map out all the transitions that are possible within the game.

An example of the adaptive songs within The Wind Waker is the centrality of the “Overworld Theme,” or the “Great Sea Theme.” It cross-fades into each of the various islands when the player approaches them. It also changes when a storm arises, when enemies appear, and when the sun sets. At night the sea is silent, until an enemy approaches and the combat music sets the stage for the action. And when the sun rises, there is a Dawn song that introduces the “Great Sea Theme.” Below is a game score graph that maps the major musical transitions of the game. These environmental songs are in rounded boxes to symbolize their looping nature.

Figure 5: Game Score Graph A; rounded boxes loop

This game score graph details the centrality of “The Great Sea Theme,” which also reveals the central role that the ocean plays in the game. This graph outlines how most of the overworld songs are looping (to create environmental music), while also tied back to the sea, the dominant symbol of this game.

Battle at sea is complicated, for some monsters merit the simple Maritime Battle music, while more difficult monsters require a more grandiose song in The Sea is Cursed. The Maritime Battle song also adapts to Link either being in the boat or out of it, when damaged by enemies 23.

Figure 6: Game Score Graph B; rounded boxes and hexagons loop

Above is an example of the musical transitions while Link is on an island, specifically the Forest Haven, which includes a dungeon. The Battle song is surrounded in a hexagon because it is unique in its nature. While it is a looping, environmental song, it is also very interactive. Whenever Link swings his sword, the music increases in tempo and additional chords (earcons) are added when he strikes an enemy. This is an impressive part of the game and adds more emotion to the battles 24. Each combo and each swing changes the song, making it unique while building upon the looping foundation.

This graph is important because it reveals a layered approach to the dungeon design. First the player starts on the ocean, but when they are near The Forest Haven, it transitions to that music. But entering the island itself and then descending into the dungeon each bring another transition to a new, but similar song. These layers of music are another example of leitmotif, as each of these songs contain similar motifs, but are used to signal transitions within the game.

And each layer of this graph also reveals the abundance of earcons and non-looping sounds. These jingles are only accessible on islands or within the dungeons, because there the gameplay changes to include finding items and more complex battles. However, this graph does not outline all the earcons of the game, there are some that occur in the overworld when Link is sailing. These music cues alert you to sunken treasure, and add to the immersion within the gameplay. As a whole, the game is very interactive with its uses of various types of music that fade into each other, or that play on top of each other, creating an experience that is real and epic.

Musical Message

Music is an important aspect of this game, as an instrument lends its name to the title 25. And while the game continues the tradition from previous games of implementing player-created-music to solve puzzles, this game has fewer songs which all blend together to me. The adaptive soundtrack, and the leitmotifs were much more powerful to me, and resonated unlike the six songs I could play on my wind waker.

From a deeper sense, the soundtrack supports a mood of anticipation. The game opens with Outset Island, where the music is light and hushed, played on wind instruments and violins. However, the melody never resolves into its tonic chord, or the triad of notes which bring completion and finality 26. Mark Hayse describes how the “Great Sea Theme” builds this anticipation for something greater to come:

Likewise, the theme song of the Great Sea never resolves into the tonic, evoking a mood of adventure. The Great Sea theme begins with the crash of a cymbal as ocean spray splashes over the ship’s bow. Waves of trombones and cellos imitate marching cadence. The Great Sea theme is much firmer than the Outset Island theme, filling the player’s heart with boldness as Link sets sail for undiscovered country. 27

While this anticipation builds the sense of adventure, exploration, and sets the game up as an epic, the soundtrack finally finds its closure in the “End Credits” song, which intertwines the various melodies of the game into a musical synthesis of many voices becoming one 28.

This soundtrack is a wonderful use of storytelling and just great sound design. There are great hits like “Dragon Roost Island,” which are still great years later. While there is so much variety—every boss battle has its own song, even when the player refights them in Ganon’s Castle—the soundtrack relies on variations of themes. “The Legendary Hero” is another great song, and its strength comes from its ability to remix the past into something familiar and new.

This soundtrack is a collection of emotion, that tries to rise above the heights of cinematic music to create something more interactive and real to the player 29. The flow of adaptive music, combined with the storytelling of leitmotifs, create a sense of an evolving mood. This story, as strengthened by the music, instills in the player a sense of awe and wonder, as Hyrule is majestic and mythical.

Notes:

- Turner, J. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Nintendo (2002). Press interview for The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. Retrieved from http://www.gamecubicle.com/interview-legend_of_zelda_wind_waker_miyamoto.htm.

- Brame, J. (2011). Thematic Unity Across a Video Game Series. Act-Zeitschrift für Musik & Performance, 2011(2), p. 9.

- Salbato, M. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Ibid.

- Brame, J. (2011). Thematic Unity Across a Video Game Series. Act-Zeitschrift für Musik & Performance, 2011(2), p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Nintendo (2002). Press interview for The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. Retrieved from http://www.gamecubicle.com/interview-legend_of_zelda_wind_waker_miyamoto.htm.

- Salbato, M. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Brame, J. (2011). Thematic Unity Across a Video Game Series. Act-Zeitschrift für Musik & Performance, 2011(2), pp. 2-16.

- Ibid.

- Glink, (2016). Why Zelda the Wind Waker Is So Influential. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZMsmetrNYyM&list=PLLOKr6vZo1nssUqnkFm2LQsr4ovtV5xRz&index=17.

- Wikipedia (n.d.).

- Puschak, E. [Nerdwriter1] (2016, February 17). Lord Of The Rings: How Music Elevates Story. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7BkmF8CJpQ.

- Ibid.

- Turner, J. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Salbato, M. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Turner, J. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Brown, M. [Mark Brown] (2014). https://www.patreon.com/posts/13801754

- Ibid.

- Medina-Gray, E. (2014). Modular Structure and Function in Early 21 st-Century Video Game Music. Yale University, p. 167.

- Ibid.

- Turner, J. (n.d.). The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker OST. RPGFan. Retrieved from http://www.rpgfan.com/soundtracks/zelda-wind/.

- Hayse, M. (2011). The meditation of transcendence within The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. In J. Walls (Ed.), The Legend of Zelda and Theology (p. 85). USA: Gray Matter Books, pp. 86-87.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Nintendo (2002). Press interview for The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. Retrieved from http://www.gamecubicle.com/interview-legend_of_zelda_wind_waker_miyamoto.htm.