Like I mentioned in my last blog post, I wanted to take some time to analyze how the mechanics of Majora’s Mask and Breath of the Wild both promote exploration, but also the weaknesses of these games. Game mechanics graphs are a visual representation I’ve come up with to break down the core elements of a game, as defined by short term and long term goals, currencies, and the mechanics that players engage with to accomplish these goals. A good game has a singular goal that players are working toward, (Monopoly is to bankrupt your opponents), and these long-term goals are accomplished through the exchange of currencies and the completion of minor goals. I’ve also analyzed the game mechanics of the original Animal Crossing game and its mobile sequel, Pocket Camp, and compared how they differ.

I’m noticing that “feature creep,” while usually used as a derogatory term for how complex games have become, is a natural part of the evolution of games. Older games (such as Animal Crossing and Majora’s Mask) have game mechanics graphs that are more simple than their sequels within their own series. Which I’m slowly starting to accept, but I also believe strongly that the simpler the graph, the better. Below is how I would define the mechanics of Majora’s Mask:

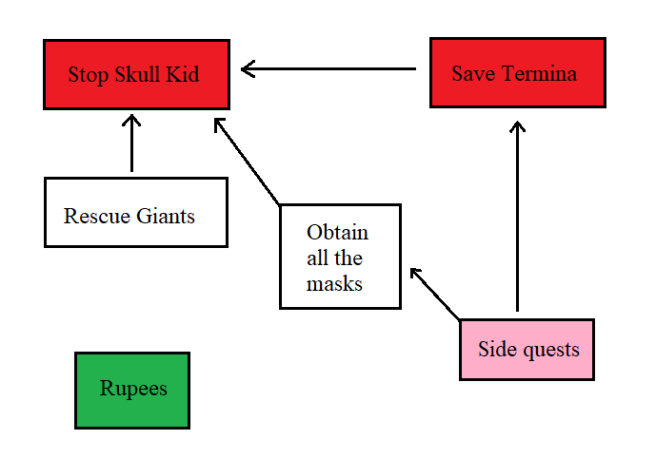

Game Mechanics Graph: Majora’s Mask

This game mechanics graph shows the basic principles of the game, through obtaining masks, completing sidequests, and saving Termina. The objectives and mechanics of this game are fairly straightforward, but I grouped them from long-term (at the top) to short-term (at the bottom). These long-term objectives are in red: save Termina (such as helping the characters and inhabitants of the world within Majora’s Mask), and stopping Skull Kid. These two objectives are of equal weight and can be done independently of each other. And a short-term objective (pink) is the completion of each side quest. These interactions that fill up your bomber’s notebook can often be done in one sitting, sometimes even within one 3-day cycle of the game.

And lastly, the currency of the game, (in green, Rupees) doesn’t contribute to any of the mechanics or objectives. It could be argued that the masks are the currency of the game, however, it is possible (and I’m sure has happened) for players to engage with the game in the entirety of the major plot points and only collect the transformation masks. Also, the masks in the game are not really used through an exchange, unlike how players trade in other currencies.

Breath of the Wild’s graph

As part of my reflection on why I don’t interact with the sidequests in Majora’s Mask or Breath of the Wild, I watched this great video by the Design Doc. In it, he described how Breath of the Wild creates an exploration cycle, where you see something glowing on the horizon (typically a tower or shrine), chase after it, and then work your way toward your larger goal, but keep getting distracted in the meantime. I know that this is how I have interacted with the game, the excellent world design has driven me to keep chasing after things that look or seem different, out of place, or unique. The Design Doc describes how the game makes use of sightlines, terrain, gameplay loops, and Korok seeds to keep you engaged.

It is also worth noting that this game mechanics graph does not contain every mechanic or gameplay element from Breath of the Wild. Rather, for simplicity’s sake, I condensed and simplified as much as possible.

Game Mechanics Graph: Breath of the Wild

In this game mechanics graph, again I’ve mapped out the objectives and mechanics from the long-term (at the top) to the short-term (at the bottom). Though technically, the major objective of the game (defeating Calamity Ganon) can be tackled at almost anytime. Hence the giant arrow of choice that connects it to most of the other mechanics. In this unique way, the player has the choice to complete this objective at any time, following the completion of the Great Plateau.

The other major objective of this game, as evidenced by its design as well as the marketing, is the exploration of Hyrule. Many of the mechanics are tied to this objective, and through the principle of exploration, the player interacts with other minor objectives. For example, wanting to discover the next region leads a player to climb a tower, atop which they discover another shrine, after which they run into an NPC which sends them on a sidequest, which then leads them to seek out the next Divine Beast, which leads to a new region, and the cycle continues. Through wanting to explore, the player accomplishes minor objectives, which also lead to a desire to explore greater.

Also worth noting is my decision to make Gear the real currency of this game, instead of Rupees. While it Rupees are used in monetary exchanges, these are few when compared to the constant exchange that happens when a player amasses new melee weapons, bows, arrows, and shields. Rather, instead of collecting Rupees, the player instead is almost always seeking out new and better gear, especially since their current gear is on the verge of breaking. This durability system ensures that the player doesn’t get complacent and is always seeking out new enemies to defeat and gear to collect.

Discovery versus Exploration

Looking at these two game mechanics graphs, and building upon my thoughts in my previous post, I feel that there are two major components to Zelda games which contribute to my experiences with them. Discovery and exploration are similar, but for the purpose of this blog post, I think that they differ in their application. I think that within the principle of Discovery is the desire to learn and interact with others. Discovery can occur as a player meets new characters and learns more about the world through this lens. Much like anthropologists, players learn and grow as they experience new cultures and feel a connection to the game world through this shared and group-like experience. Discovery is at the heart of Majora’s Mask, and while open-ended and an application of paidia, it doesn’t really meet my needs. Hence I rarely engaged in the side quests of that game.

Exploration, on the other hand, seems to be a more individualized experience, where the player performs experiments and through trial and error uncovers new ideas and experiences in the game. Exploration centers on the player itself, on what they enjoy, and how important they are in the world and the play experience. Exploration is deciding “what happens when I do __,” or “what is on the other side of this mountain?” This principle is what drives me to engage with and enjoy Breath of the Wild, as I feel like an adventurer who is close to making a new discovery but doesn’t care too much about building the lore of the game or chatting with NPCs.

In closing, these blog posts and this experience of mapping out the game mechanics of these two games have helped me better understand why I interact with these games, what I want out of them, and how they work.